Review of “Want to Start a Revolution?” (NYU Press, 2009)

For centuries, history was taught as the history of great, powerful, elite men. While historical writing has become far more diverse in recent years—entire fields focus on cultural and social transformations, as well as the history of women and oppressed communities—on certain subjects the “Great Man” theory stubbornly remains. One such arena is the Black Freedom Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, which in schools across the country is either still reduced to the tactics of a single individual—Martin Luther King, Jr.—or at most a few other men.

The durability of this myth is not because of an absence of literature. In fact, a considerable body of literature exists that shatters the old myths of women as docile, provincial and uninterested in politics. Charles Payne’s 1995 “I’ve Got the Light of Freedom” on the organizing of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee in the Mississippi Delta region proved just the opposite: that women were “frequently the dominant force in the movement.” Belinda Robnett’s “How Long? How Long? African-American Women in the Struggle for Civil Rights” developed a theory that women functioned as the unofficial “bridge leaders” in the southern movement, providing the vital connection between the community and the official organizational leadership.

These works helped promote a whole trend—usually led by Black women scholars—on the experiences of women in the Black liberation, feminist, and gay liberation movements. In addition, biographies and autobiographies of key Black women activists have come out in recent years, revealing a cast of new heroines and causing re-evaluation of old ones. Anyone paying attention now knows that Rosa Parks was, for instance, an experienced activist and organizer, not an apolitical old woman who was just too physically tired to move to the back of the bus.

A recently published essay collection—“Want to Start a Revolution: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle”—continues this trend, and expands it in several significant ways. For one, it challenges the notion that the post-WWII Black liberation struggle can be separated out into neat phases, which women experienced in completely distinct ways. This runs counter to Payne and Robnett, who both identified a certain southern community-based “organizing tradition” that facilitated women’s participation, particularly in SNCC. For them, the turn towards Black Power—which appeared more masculinist and hierarchical—took such leadership and organizing opportunities away from women.

Secondly, “Want to Start a Revolution” argues—through several examples, including that of Rosa Parks—that women were not always behind-the-scenes “bridge leaders,” but often strategists, mentors, theoreticians, and formal leaders. While it is critical to discuss how sexism limited women’s possibilities in the movement, the editors argue that such an emphasis has actually obscured the leading positions women were able to achieve. While few people today recognize the names of Esther Cooper Jackson, Gloria Richardson, Victoria “Vicki” Garvin, Shirley Graham DuBois, Florynce Kennedy, Yuri Kochiyama, or Johnnie Tillmon, in their day many activists sought their advice and assistance. They have rarely been mentioned in the official history books.

Thirdly, the collection challenges the conception of Black feminism that identifies it strictly with the creation of separate organizations. While Black feminism is typically associated with the Third World Women’s Alliance and the Combahee River Collective, which formed largely in reaction to racism and sexism within social justice movements, “Want to Start a Revolution” highlights the critical roles Black women played in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s within civil rights, labor, left-wing and women’s organizations—including majority-white ones. In such history we can also discover the predecessors of what was later called “Black feminism.”

The collection covers 14 separate women leaders—and admittedly leaves out dozens of others. We offer below three examples of the activists included.

Not just ‘Black Politics’ (Vicki Garvin)

Vicki Ama Garvin was a labor leader, agitator, organizer and mentor for scores of activists in the Black liberation movement.

Contrary to popular belief, it fought against “machismo” and sexism from within by the promotion of female leadership. Victoria “Vicki” Ama Garvin destroys traditional views of Black women’s participation in the social justice movement. Garvin refused to be confined to any particular issue. She participated actively in a range of justice movements, believing all forms of oppression are integrally linked and must be fought equally.

Garvin’s political career began in the labor movement as a union organizer. Even during the McCarthy era, she remained strong in her struggle for equality and opportunity for female and Black workers. In 1947, she joined the Communist Party and in 1951 became Executive Secretary of the New York City chapter of the National Negro Labor Council.

As the anti-communist witchhunt gained momentum throughout the United States in the late 1940s and early 1950s, it took a severe toll on Garvin politically and personally. The growing anti-colonial movements across Africa inspired many Black activists in the United States and many decided to relocate to the continent during the 1950s and 1960s. In the late 1950s, Garvin traveled through Africa, where she witnessed first-hand the struggle against neocolonialism. Settling in Ghana in 1961, Garvin drew upon her activist experience to provide camaraderie and mentorship to other Black radicals.

With Malcolm X, who Garvin had known from Harlem, she referred to herself as his “mother hen”—marking her role “as knowledgeable elder (a role long gendered male) within the [B]lack liberation movement, mentoring a younger generation just as she had been mentored.” (85)

Garvin actively participated in organizations garnering support for China. During her visits to the country, she like many African American activists felt a strong sense of solidarity to the revolution there. Not only had China overthrown centuries of colonialism and put the oppressed people in power, it explicitly identified with and supported the Black liberation struggle in the United States.

Upon her return to the United States in the 1970s, Garvin functioned as an organizer and mentor for scores of activists in a whole variety of social justice causes up until her death in 2007. As Dayo F. Gore comments, “her distinct political legacy rests not in official titles but in revolutionary experience and solidarity efforts that always combined local organizing with a global vision.” (73)

Black Power and the feminist movement (Florynce Kennedy)

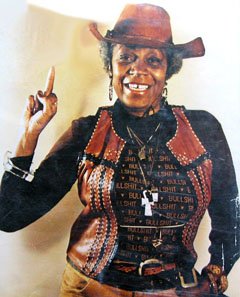

With her distinct, provocative style, Florence “Flo” Kennedy was a bold fighter for Black liberation, women’s equality, and LGBT rights.

Female Black leadership is often reduced to participation in one of two struggles: Black liberation or the feminist movement. While both are expressions of the same desire for equality, they are often separated as two independent or even opposing struggles. The case of Florynce Kennedy demonstrates otherwise. Although the most prominent Black feminist of the 1960s and 1970s—struggling inside the National Organization of Women and famous for dramatic in-your-face street theater tactics—Kennedy is virtually unknown today.

Rather than be trapped by the rigid theoretical labels that kept various social movements divided, Kennedy promoted unity in action between different groups, often inviting members of one to join the other.

Sherie M. Randolph explains that her gender never interfered with participation in the Black Power movement. She writes, “Despite her critiques of Black Power [for the political appeals to Black masculinity] and her close relationship to the feminist struggle, Kennedy continued to work inside the Black Power movement as a lawyer for Black Power leaders H. Rap Brown and Assata Shakur, as a fund-raiser for numerous Black Panther Party political campaigns, and as an organizer and delegate of the Black Power Conferences.” (225)

Kennedy used her experience within the Black liberation movement to train and educate female leadership, particularly leaders of NOW. Now leader Ti-Grace Atkinson, a white woman, reflected, “[Kennedy] had a profound…influence…on some of us…we were observing and we copied [Black leadership]” (236). Kennedy also fought tooth-and-nail against the expressions of racism within the burgeoning feminist movement. When Kennedy and Atkinson organized a “Black Power and Women” panel for the New York NOW chapter, they found NOW leaders ignoring, and even mocking, the statements and contributions by Black women. (239)

Kennedy and Atkinson’s open identification with Black Power and their desire to move NOW in a radical direction led to a split in the New York Chapter’s 1968 election. The proposals of Florynce Kennedy and Ti-Grace Atkinson to radicalize the organization were overwhelmingly defeated. Atkinson, who had become the chapter president, resigned from the organization and was joined by Kennedy.

While Kennedy understood the need to work within varying movements, she would not tolerate an organization that compromised or minimized the oppression of Black people. As she explained, “Racism will always be worse than sexism until we find feminists shot in bed like [Black Panthers] Mark Clark and Fred Hampton” (229). This does not mean Kennedy was in the business of weighing oppressions—she actively fought for gay rights, Black liberation, and women’s equality. Rather, she understood the historic and pivotal role of the Black struggle.

Upon leaving NOW, Kennedy remained an ardent fighter—as she would be for the rest of her life. She, Atkinson and others formed the October 17th Movement, which “reflected Kennedy’s concern that the feminist movement concentrate on the connections between sexism, imperialism and racism” (242). She passed away in December 2000.

Asserting women’s leadership (Denise Oliver)

The Young Lords Party was an organization formed in the late 1960s by Puerto Rican youth who modeled their party on the principles and structure of the Black Panther Party. Like the Panthers, they advocated the self-defense and empowerment of the cities’ most oppressed urban communities, and put forward revolutionary socialism as the path to liberation.

Although centered in the Puerto Rican community, the YLP membership crossed ethnic and cultural lines, including non-Puerto Rican Latinos and African Americans. Denise Oliver was one such African-American woman, who joined the YLP after growing up in New York City’s Puerto Rican communities and after already been an activist briefly with SNCC.

From an early age, the importance of a unified revolutionary movement was instilled in Oliver by her radical parents, who were part of the Communist Party mileu. “A number of white leftists who are red babies… had that kind of upbringing,” she recalled. “I’m one of the black red babies. And there were a few of us.” (274)

The struggle to integrate New York City public schools in the 1950s quickened young Oliver’s political development. The North was often categorized as a place of escape the treacherous racism of the southern United States, but this was not the reality. New York City’s efforts to bus Black and Latino students to predominantly white areas in Queens, for instance, sparked a massive racist response that Oliver experienced first-hand. Oliver recalled getting off the bus to see students fighting in the yard: “you could feel the hostility immediately.” (275)

As a young activist, Oliver sought out organizations that were directly involved in the struggle against racism and exploitation. While her parents were around the Communist Party, Oliver yearned for more direct action. Her search for participatory politics led her to various organizations, including SNCC and CORE. During an education program in New York, Oliver joined the Sociedad de Albizu Campos. This reading circle, named after the father of the Puerto Rican national independence movement, Don Pedro Albizu Campos, would become the New York chapter of the Young Lords Party.

Author Johanna Fernandez suggests that African-Americans, Panamanians and other non-Puerto Rican members were not merely members of the YLP “but were integral to its lifeblood.” (282) Oliver was in fact the first woman elected to its Central Committee. Her membership and leadership within the organization reflected the organization’s belief that oppressed people of color in the United States had a common struggle. While the capitalist class and its media like to promote divisions between nationalities, groups like the YLP pointed to common exploitation to advocate solidarity and mutual understanding.

In its beginnings, the YLP advocated “revolutionary machismo” in its political program and women held no top leadership roles, but over time the women members were able to challenge these shortcomings.

Oliver herself had not confined to a purely administrative role within the Young Lords Party. This was in no small part due to her upbringing. She recalled, “I didn’t want to learn how to type because I didn’t want to be typecast.” (285). She did not want to become another secretary.

She quickly gained knowledge of the organization on the national level and learned the skills required for leadership from other cadre within the Party. These attributes propelled her to the Central Committee after women demanded representation in the leading body of their organization.

Oliver’s leadership within the Young Lord’s Party did not eradicate the problems of sexism within the organization; instead her role opened the door for an open debate around female oppression in society and within the party. Following Oliver’s election, a women’s caucus was formed within the party to address these issues directly.

Oliver explained the complex problems of trying to overcome sexism: “Part of the problem wasn’t just that men automatically took the sort of macho role, but [that] women were used to submissive behavior…and weren’t opening their mouths.” (286) This orientation sparked the publication of “La Luchadora,” marked with the task of speaking to women’s issues within the organization and the oppression facing women in the community as a whole.

Denise Oliver was one example of how the Black liberation movement directly engaged with and helped nurture the movements of other oppressed people. As an African American woman worker who helped lead an organization focused in Puerto Rican communities, she proves what is a central point of the overall book: that many revolutionary activists and organizations defy the simple boxes that many historians try to put them in.

How can we correct the history books?

Clearly, the history of the Black Freedom Struggle can only be accurately told if it includes the leadership roles played by women. Want to Start a Revolution joins an ever-growing body of literature that disproves the “Great Man” descriptions of this era.

But if the information is out there and published, one must ask: Why do such descriptions—in fact, myths—continue to dominate? At a certain point, the problem is not principally one of lacking historical research. The way history is told is in fact a political problem.

Most high school textbooks will flatten the Black liberation struggle to this or that leader, usually Martin Luther King, Jr. This leader’s more radical ideas will be stripped away and he—for it is always a “he”—will thus be converted into a safe, memorable icon. Malcolm X is raised—if he is raised at all—as the yin to Martin’s yang, the embittered and violent radical versus the “turn the other cheek” good pacifist. This is a false history, and yet it still prevails.

It is the same problem with the history of women in the Black liberation struggle (and many other struggles). The examples of strong, leading, revolutionary women—especially Black women—simply do not conform to society’s patriarchal and racist norms. As such, we must carry out a political struggle today to demand our true history be taught—and ultimately fight for a new system that puts workers and oppressed people in control of educational institutions.

Setting the record straight will require something more than writing history; it will require us to make it.

“Want to Start a Revolution: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle” (NYU Press, 2009) is edited by Dayo F. Gore, Jeanne Theoharis, and Komozi Woodard.