Editor’s note: This article originally appeared on Liberation News.

The full story of the struggle to end chattel slavery in the U.S. has yet to be fully told. History books have always minimized the struggle of enslaved people, who from the beginning in 1619 in North America, fought slavery at every turn, rebelling, escaping, fighting for the right to fight. Some 180,000 enlisted in the Union army and suffered among the highest casualties in a war where high casualty rates were considered proof of bravery.

The role of white working-class people in the struggle against slavery has also been left out of history books, buried beneath an avalanche of lies, distortions and slander. The ruling class is terrified of multinational solidarity, particularly in the working class. Their history is meant to show that such solidarity is not today, nor ever, possible. The truth is hidden.

“Labor in the white skin can never free itself as long as labor in the black skin is branded.” — Karl Marx, Capital

Marx saw clearly that the white working class had a direct stake in the struggle against slavery, that slavery in the South was closely linked to the exploitation of the working class in the North.

History books focus on the role of bourgeois abolitionists, often based on religious moralism and sentiment. Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” who portrayed Tom as a passive, Christ-like figure, and William Lloyd Garrison, the editor of the abolitionist newspaper “The Liberator” organized and bravely faced death threats. But it was the active role of white, working-class abolitionists in the struggle against slavery that mattered more. The truth is that alongside the heroic efforts of enslaved Black people, a great many white abolitionists were ready, willing and able to put their lives on the line to end slavery.

Struggle against slavery started in 1619

The struggle of enslaved people in North America began from the first day African captives were forced off the slave ships in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619, and never stopped. From mass rebellions, escapes, sabotage, and countless other ways, enslaved people fought for their freedom. Rebellion never stopped, whether individually or in larger groups. It is not possible to provide a complete list of rebellions because they were so many, and no one article can do full justice to the struggle. Here are just a few:

The best known is Nat Turner’s heroic revolt in 1831, when Turner and his group escaped and moved from plantation to plantation, gathering more followers until they numbered about 60. They took money, supplies and weapons as they moved and killed 55 white slave owners and their families. Contrary to most reports that said that the rebellion was against all whites, Turner spared homes of poor whites “because Turner believed that the poor white inhabitants ‘thought no better of themselves than they did of the slaves,’” according to one newspaper of the time.

When captured, the State of North Carolina executed 56 Black people; the racist militia killed about 200 more, whether they had been involved in the rebellion or not.

Andry’s Rebellion in 1811 involved more than 200 people and burned at least three plantations. In the The New York City conspiracy trial of 1741, 10 fires were set in New York City as part of a plan to end slavery. Thirty African American men, two white men, and two white women were executed after a phony “jury” trial. In the 1739 Stono Rebellion in South Carolina, enslaved people escaped and killed several slaveholders, burning their homes as they traveled.

Denmark Vesey (also called Telemaque) was a Black leader in Charleston, South Carolina, and worked as a carpenter. In 1822, Vesey was alleged to be the leader of a planned slave revolt. Vesey and his followers were said to be planning to kill slaveholders in Charleston, liberate the slaves, and sail to the Black republic of Haiti for refuge. In June of 1822, he was convicted of being the leader of “the rising.”

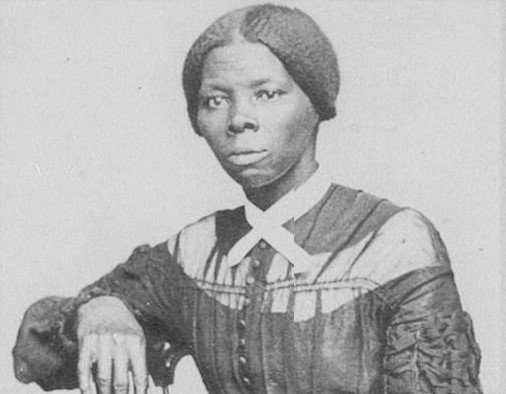

Harriet Tubman was an escaped enslaved woman who became a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, leading enslaved people to freedom before the Civil War, all while carrying a bounty on her head. But she was also a nurse, a Union spy during the Civil War, and a women’s suffrage supporter.

In 1863, Tubman became the head of an espionage and scout network for the Union Army. She provided crucial intelligence to Union commanders about Confederate Army supply routes and troops and helped liberate enslaved people to form Black Union regiments.

One of the most successful expeditions to free enslaved people was the Combahee Ferry raid, which freed over 700 people, led by Harriet Tubman, carried out by 300 Black Union soldiers and Kansas Jayhawker Colonal James Montgomery.

The true story of working-class abolitionism is yet to be told

The entire history of the working class, particularly regarding the struggle against slavery, has been re-written to fit the needs of the captains of capitalism. The following are only some examples of how history has been rewritten. This information is available but hard to find and never part of the popular media, where it belongs.

The struggle in Kansas against slavery led by abolitionist Jayhawkers

Fiction: Today a “Jayhawk” is a fictional blue bird and mascot of the Kansas athletic teams. Jawhawkers in pre-Civil War history are most often called “robbers” “assassins” and “looters” not concerned about slavery. A Hollywood movie in 1959 called the “Jayhawkers” had no Black actors and had no reference whatever to the Civil War.

Fact: The struggle against slavery in Kansas in the 1850s, before the Civil War, was led by an unofficial, unsanctioned abolitionist force called the Jayhawkers, who fought a border war with the slave owners and their hired thugs. The Jayhawkers refused to join units officially sanctioned by the U.S. Army, since the government policy was not anti-slavery until 1863.

The Jayhawkers conducted raids into pro-slavery Missouri to stop the attempt of pro-slavery forces to invade Kansas and make it a slave state.

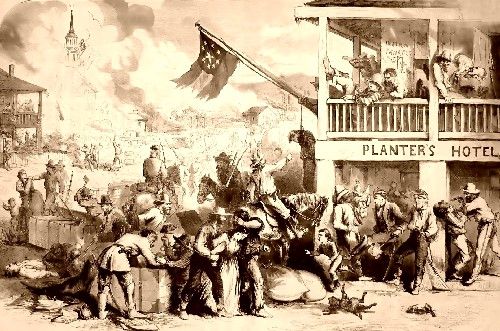

One highlight of their struggle was the sacking of Osceola, Missouri, a center of pro-slavery forces. It was done by the Kansas Jayhawkers on Sept. 23, 1861, to push out pro-slavery thugs, after the Union Army left the territory. It was not authorized by Union military authorities, but the town of Osceola was virtually burned to the ground and over 200 enslaved people were freed. Twelve slave owners and slave catchers were rounded up, given a quick trial, and nine were executed. What’s not to like?

John Brown fought in Kansas and led raid on the armory at Harper’s Ferry

Fiction: John Brown was “insane,” “mentally unstable,” “psychotic” and so on.

Fact: Implying that any white man willing to fight and die to end slavery was “insane” fits the racist narrative of the slave owners, and is a terrible insult.

After the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, the issue of slavery was left up to the white, male settlers. Pro-slavery gangs invaded Kansas. John Brown moved to Kansas and was an early Jayhawker. He lead abolitionists to Pottawatomie Creek in retaliation for a raid on the Free Soil town of Lawrence. Brown and his followers killed five pro-slavery thugs with their own swords (!). It has been called “murder” and a “massacre,” the usual names for revolutionary justice. Brown was involved in numerous raids to aid enslaved people before his daring raid on Harper’s Ferry with 13 white and five Black men, which became a world-famous call for a war on slavery.

Brown’s famous words on the gallows tell the real story: “ … had I so interfered on behalf of the rich, the powerful … or any of that class. … Every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.”

Northern trade unions went all in on the Civil War

Fiction: Most Union soldiers were racist and only fought because of the draft and to “save the Union.”

Fact: When the Civil War started in 1861, so many workers volunteered for the Union Army that whole unions in the north virtually ceased to exist. Irish workers, immigrating from famine at home, “had a battle record second to none.” Some 200,000 German workers, many immigrants from the crushed revolutions of 1848 in Europe, who settled in St. Louis, brought their revolutionary spirit with them to battle the slaveholders. Refugees from the 1848 revolutions came from other countries as well. English Chartists (a working-class movement for reform in the 1840s), Welsh miners, 40,000 Canadians, the Garibaldi Guard of Italian workers in New York City, and so on, volunteered by the many thousands. But none surpassed the 186,000 Black soldiers, mostly freedmen, who volunteered to fight when finally allowed to enlist in 1863. (Labor’s Untold Story, United Electrical Workers of America, 1955)

This is not to say that there wasn’t any racism among Union soldiers, reflecting the prevailing attitudes in the North. The Democratic Party, for example, controlled by slave-owning interests, pulled no punches in its racist depictions in political campaigns, stating that if slavery ended the freedmen would come north, steal jobs, and lower wages, not unlike the Trump administration says today. Actually the opposite was true. Ending slavery strengthened the hand of labor.

Fiction: All Confederate soldiers loved General Lee, were happy to fight for the slave-holding planters, and had high morale, unlike the Union Army.

Fact: Certainly the Confederate Army was a cesspool of racism, from the officer corp. through the ranks. But the desertion rate in the Confederate Army was even higher (10-15 percent) than the Union Army (9-12 percent).

Almost completely unknown was the anti-Confederate guerilla war in Mississippi led by a poor white farmer, Newton Knight, who organized several hundred Confederate deserters to declare Jones County to be a “Free State” that seceded from the Confederacy. If Knight hadn’t spent years after the Civil War in seclusion, finally calling a journalist to record what happened, his story would have been buried forever.

Experience in the Civil War changed consciousness among Union soldiers

Consciousness changes in any struggle. When the Union soldiers saw how horribly enslaved people were treated, sentiment for abolition grew; when they saw the widespread poverty in the South, for enslaved people as well as poor whites, abolitionism grew; when Confederate officers arrogantly entered Union camps to demand the return of “their” escaped slaves, abolitionism grew; and when white Union soldiers saw the unparalleled bravery and fighting spirit of Black soldiers, sentiment for abolition grew.

In 1864, when the election was a referendum on the war, between Lincoln and the pro-slavery Democrat, formerly popular Union General McClellan, the soldiers’ vote was at least 80 percent for Lincoln, 90 percent by some accounts. (What They Fought For, by James M. McPherson, 1995)

Suspect history of the racist anti-draft riot of 1863 in New York City

The racist uprising in New York City against the Union draft law was mostly Irish immigrants, who blamed Black people for unemployment, burned, looted and lynched for four days, burning an orphan asylum. That wealthy men could buy their way out of the draft for $300 (while a skilled worker could earn $10 a week) was somehow blamed on the free Black community.

However, New York City at the time was a hotbed of “copperheads,” supporters of slavery in the North. The biggest banks in New York City were intimately connected with the Confederacy, and their profits largely came from slavery. The list of banks involved reads like a “who’s who” of Wall Street: JP Morgan, Bank of America, Lehman Brothers, Wachovia Bank, Wells Fargo, and other banks all got rich from the slave trade.

The Irish population of New York City in 1850 was about 200,000; about 1,200 to 1,500 took part in the racist riot. The U.S. government today enables well-financed racist militias to roam freely; it is hard to believe that the banks had no hand in financing lumpen elements in the working class to lead the revolt. As was mentioned, Irish soldiers had a strong war record in the Civil War.

Even the history of piracy has been completely re-written

Fiction: Pirates were bloodthirsty killers who made their captives “walk the plank.”

Fact: Real pirates, whatever their individual stories, were democratic and egalitarian, and played a role in the struggle against slavery: The most famous pirate ships in history were captured slave ships. Blackbeard’s Queen Anne’s Revenge and Samuel Bellamy’s Whydah were both stolen from slavers and turned into pirate vessels.

When a pirate crew captured a slave ship, they got a whole new crew. Often, they’d go into the lower decks, set the slaves free, and encourage them to join. Blackbeard, for example, had 60 Black crew members on a ship of 100 men. On pirate ships, all crew members, Black and white, had the same rights.

International Workmen’s Association (First International) tried to continue struggle

In September 1871, 20,000 people marched for the eight-hour day in New York City, with the slogan “Workingmen of All Countries Unite.” African American members of the waiters’ union and plasterers’ union joined the march to great applause. This was a real advance in the city where eight years earlier racist anti-draft riots killed and destroyed the homes of Black people. (James Allen, Reconstruction: the Battle for Democracy 1865-1876. New York: International Publishers)

But the forces of racism and reaction were to overwhelm the progressive movement. Union troops were withdrawn from the South in a historic betrayal of the freedmen in 1876. The Panic (depression) of 1873 brought renewed workers’ struggle in the North. Some of the troops withdrawn from the South were used against the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, killing over 100 workers in several states.

History is re-written to protect the powers that be

All movements look to the past for inspiration, and the current rebellion today against racism and police murder is no exception. Solidarity is a critical component of every movement. Workers on strike need and depend on solidarity from other workers, for example. The ruling class is not very afraid of middle-class movements because they know the middle class is not revolutionary on its own. They are terrified of working-class movements and the solidarity that comes from common class interests because they are all too aware that workers are the true grave-diggers of capitalism. We all have a stake in the struggle against racism and national oppression.