“In contradistinction to German fascism, which acts under anti-constitutional slogans, American fascism tries to portray itself as the custodian of the constitution and ‘American democracy.’”

– Georgi Dimitrov

Introduction

Six months ago, on January 6, 2021, a racist mob, incited by outgoing U.S. President Donald Trump, stormed the U.S. Capitol in a chaotic attempt to prevent the congressional certification of the 2020 presidential election results, a necessary step before the inauguration of Joe Biden.

The assault on the Capitol was led by militarized fascist groups composed of many current or former military and police [1]. Some of the leaders of the organizations involved, such as Proud Boys Enrique Tarrio and Joseph Biggs, had direct ties to U.S. intelligence agencies, having served as FBI informants [2]. Only one fifth of Capitol Police were on duty that day, and they were unprepared and underequipped, even though the U.S. national security state had advance knowledge of the plot. A Senate investigation concluded that there was a multi-teared security “failure” on January 6th that involved not only Capitol Police but also the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Defense, among other agencies: Capitol Police were seen opening barricades and fraternizing with fascists, there were delays in deploying the National Guard, restrictions on reinforcements came from on high (implicating Defense Secretary Mark Esper and Secretary of the Army Ryan McCarthy, amongst others), DHS agents on standby were not deployed, etc. [3].

Much is still unknown about what was actually going on behind the spectacular scenes of the storming the Capitol. The fact that the bourgeois media ran an expansive faith-in-government campaign in its wake, and Senate Republicans blocked plans for a bipartisan governmental commission to investigate it, has only contributed to the obscurity surrounding this event. Essential questions remain: Although there are clear signs of governmental involvement, how deep and wide was the conspiracy? Which precise factions of the capitalist ruling class backed the organizations behind the assault on the Capitol, and to what extent was it “astroturfed” by them (meaning discretely funded to create the illusion of a grassroots movement from below) [4]? What was the exact ratio and relationship between state agents and the para-state—i.e. vigilante—actors involved [5]? Was this solely an organic conflict between the Trump and Biden camps, or was something more at play? It is important to note in this regard that the PR campaign that ushered Biden into office as the “savior of our democracy” has empowered his administration to break countless campaign promises and use the storming of the Capitol as a pretext for pushing for increased securitization, surveillance and the criminalization of dissent (which have always been used to target the Left).

Whereas serious and rigorous investigations will need to take place in order to resolve these questions, a scantly known fascist plot to seize control of the U.S. government in the 1930s sheds important light on the history of homegrown fascism and the clandestine machinations of the bourgeoisie. Although there are significant differences between these two events, and facile analogies should be avoided in the name of precise materialist analysis, knowledge of the details of the earlier plot can help us better understand the relationship between bourgeois democracy and fascist movements in the U.S. settler colony.

A proven fascist conspiracy in the U.S.

In 1934, the McCormack-Dickstein Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives, after weeks of investigation, concluded that “certain persons had made an attempt to establish a fascist organization in this country” [6]. The American Liberty League, as this organization was known, served as the driving force behind what the bourgeois press described as an outlandish plot of “Wall Street interests to overthrow President Roosevelt and establish a fascist dictatorship, backed by a private army of 500,000 ex-soldiers and others” [7]. Although the plotters ultimately failed, due in no small part to the strength of the domestic and international communist movement, as well as popular support for the New Deal, the McCormack-Dickstein Committee reached a clear conclusion: “there is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient” [8].

It is thus part of the public record that a fascist seizure of state power had been planned in the U.S. The fact that few people are aware of this reality serves as a chilling reminder of the power of bourgeois history, through schooling and the media, to expunge—or at least bowdlerize—the historical record, thereby promoting the myth of far-away fascism, or even the patently false idea that fascism “can’t happen here.” This labor of rewriting history began, as we will see, with the McCormack-Dickstein Committee’s own efforts to suppress evidence, diminish their findings and avoid prosecutions.

Nevertheless, it is clearly the case that there have been, and continue to be, fascist movements in the U.S., and the 1934 “business plot” is one instance when a complete seizure of state power was envisaged by a major segment of the capitalist class. This event is therefore stocked full of important lessons for the ongoing socialist struggle against fascism and its wellspring: capitalism. The inner workings of this plot have much to teach us about the conspiratorial activities of the ruling class, its internal factions and diverse tactics, its use of well-paid lackeys as political leaders, its financial and ideological manipulation of segments of the working population, its wily construction of political spectacles, its vast control of the press, and its malicious production and dissemination of public history. They also demonstrate the crucial importance, for fighting fascism, of the organized workers movement, the international socialist project, tactical gains for the masses within bourgeois democracy, militant journalism by communists and fellow travelers, and historical materialist analysis of actually existing bourgeois democracy. Although the historical conjuncture has changed, these lessons are just as important today as they were in the 1930s.

International and national contexts

To fully understand this fascist plot, it is imperative to situate it within global class struggle. In the 1930s, the capitalist system was reeling from the drastic consequences of the Great Depression and was facing the greatest threat to its existence in the successful establishment and development of the first socialist workers state in the U.S.S.R. It is in this context of the material and ideological crisis of capitalist legitimacy that big industrial capital in Europe and the U.S. had begun backing fascist movements as a final solution to class struggle. A significant faction of the bourgeoisie, and in particular large industrial capitalists, hoped to be able to fund a false revolution from below in order to beat back the workers movement, destroy communist party organizing, and decisively shift the balance of power between labor and capital in their favor.

Like all other capitalist countries in the wake of the crash in 1929, fascist movements were in full swing in the U.S. In fact, when Italian fascism appeared on the world stage, many Americans recognized it as a European version of the Ku Klux Klan, which itself was part of a broader network of anti-labor vigilante groups and self-proclaimed fascist organizations like the Sentinels of the Republic, the Crusaders, the Silver Legion of America, the German American Bund, and Friends of New Germany. In Facts and Fascism, journalist George Seldes examined in great detail the similarities between fascist movements abroad and those in the United States since in both cases big capital directly invested in reactionary political groups, controlled the mainstream press and major social institutions, and sought to mobilize sectors of civil society around ultra-nationalist, racist, imperialist and anti-communist ideologies that ultimately served the interests of the capitalist ruling class.

Impoverished war veterans were one of the targeted populations, just like in Italy, and the American Legion became one of the most powerful supporters of fascism. Beginning in 1922, it invited Mussolini to nearly every one of its conventions, and in 1935 it made him an honorary member of the Legion. As one of the first commanders of this veterans’ organization, Alvin Owsley, explained:

“the American Legion stands ready to protect our country’s institutions and ideals as the Fascisti dealt with the destructionists who menaced Italy! […] The American Legion is fighting every element that threatens our democratic government—Soviets, anarchists, I.W.W.’s, revolutionary socialists and every other ‘red” [9].

Indeed, the reds were involved in expansive anti-fascist, pro-worker organizing, and many veterans became involved in the struggle. One particularly significant event, which serves as essential background for the planned fascist takeover, occurred in 1932. Anywhere from 17,000 to 25,000 veterans formed a Bonus Expeditionary Force (BEF), or “Bonus Army,” and marched on Washington to demand that their “adjusted compensation” for time served be paid immediately. Congress had voted in 1924 that WWI vets would receive compensation for each day served, but it delayed the disbursement of most of the funds until 1945. Under the crushing weight of the Great Depression, the BEF demanded immediate payment, setting up camp near the Capitol.

Felix Morrow, a reporter at the time for the Communist Party’s New Masses, provided an eye-witness account of class struggle within the encampment, which was also discussed by CPUSA’s Central Committee in their 1932 statement “Lessons of the Bonus March.” On the one hand, there were the communists within the Workers Ex-Servicemen’s League (WESL), who had taken a leading role in the National Hunger March on Washington in 1931. They provided militant leadership for the movement and raised the additional demand “for complete equality for Negroes and the abolishing of all discrimination of every sort” [10]. As many remarked at the time, the BEF and their encampment were integrated—in stark contrast to the racial apartheid that characterized American society at large and the military—and there were frequent scenes of fraternization between white and Black veterans [11].

This was perfectly in line with the CPUSA’s larger platform of social and economic equality, which was spelled out in no uncertain terms in the same issue of The Communist that published “Lessons on the Bonus March”:

“The Communist Party fights for the unity of the entire working class, Negro and white, native and foreign born, male and female, adult and youth, the unemployed and the employed. The Communist Party not only fights for the interests of all the workers, but also puts forward special demands in the interests of those sections of the working class that are discriminated against—the Negro masses, the women workers, etc” [12].

On the other hand, opposed to the advocates for equality, there was a group of “petty bourgeois demagogues,” according to the CPUSA, who embodied “the fascist tendencies which endeavor to divert the radicalization of the petty bourgeoisie” [13]. They were led by Walter W. Waters, the superintendent of a fruit canning factory, who surrounded himself with an assortment of police officials and undercover agents [14]. Demonstrating the porosity between state and para-state actors in many fascist and semi-fascist movements, Waters’ group worked hand-in-hand with the official police force, politicians, and the capitalist press to try—unsuccessfully—to seize control of the movement. In fact, the group made important decisions in direct consultation with General Glassford, the Superintendent of the District of Columbia’s Metropolitan Police Department.

Anticipating what would later become known as COINTELPRO, numerous governmental and law enforcement agencies had been spying on radicals, infiltrating their organizations, and attempting to co-opt demonstrations as part of their efforts to destroy communist and other progressive movements by any means necessary. The agencies included: the Army’s Military Intelligence Division (MID), the Office of Naval Intelligence, the Secret Service, “Red Squads” in city police departments, and the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Investigation [15]. One of the chief subversive hunters in the MID was General MacArthur’s trusted subordinate, Brigadier General George Van Horn Moseley, who “saw in the integration of black and white veterans” in the BEF “living proof that ‘Negro and Jewish’ Communists were planning a revolution” [16].

In what appears to have been a dress rehearsal for the 1934 “Business Plot,” Waters announced in 1932 that he had been approached by a group of wealthy elites who offered him financial assistance if he would be willing to transform his followers in the BEF into a permanent “Fascist Army.” Directly comparing this potential militia of veterans to the Fascisti and the Nazis, Waters explained that they were to be called the “Khaki Shirts,” and their role would have been to “stand between the constitution and the forces of anarchy [i.e. the reds]” [17].

One of the most well-known advocates for the veterans, General Smedley Butler, who would later play a pivotal role in the fascist plot, visited the encampment and expressed his support for the BEF (though he was identified by the CPUSA as being on the side of the reactionaries). After Congress rebuffed the BEF’s demands, many of its rank-and-file members—particularly those galvanized by the WESL—refused to follow General Glassford’s proposal to evacuate, which Waters eventually supported. President Hoover then decided to use state violence to crush the movement, claiming that it was “composed largely of Communists and criminal elements” [18]. He conferred this ignoble task on some of the rising stars of the U.S. military establishment: Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur, his young aide Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Major George S. Patton. After a brutal assault with bayonets, tear gas, and tanks, they proceeded to burn the encampment to the ground [19].

Public outcry over the use of extreme state violence against the multinational and diverse grouping of poor veterans demanding redress helped usher in the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in November 1932. Under pressure from the militant domestic workers’ movement and in the context of the rising prestige of the Soviet Union, FDR began implementing the New Deal in the spring of 1933. This government program sought to stabilize the capitalist economy, favoring the interests of big business while simultaneously including provisions for the working and toiling masses in order to stave off revolution [20]. It was, in short, a class compromise that contained important gains for certain sectors of the working class, while still protecting the principal interests of the bourgeoisie. FDR refused to pay the bonus to the veterans, for instance, or push for a bill against lynching, and he reappointed MacArthur as Army Chief of Staff.

Militant socialists and communists had already taken it upon themselves to respond to the crisis of the Great Depression through expansive organizing endeavors, which included significant movements to stop evictions, the establishment of Unemployment Councils all over the country, and an intense wave of strikes that involved some million and a half workers in various industries in 1934 [21]. It is in this context that a major segment of the U.S. capitalist class, which had extensive ties to Italian fascism and Nazism, came to the conclusion that a fascist dictatorship was the best solution to the crisis.

The plotters

Formed in 1934, the American Liberty League was a political organization composed primarily of wealthy business elites and high-profile political figures opposed to the New Deal. It included, in addition to several commanders of the American Legion, representatives from the major families of the ruling class, including Morgan, Du Pont, Rockefeller, Pew and Mellon [22]. According to Jules Archer, it formed “affiliations with pro-Fascist, antilabor, and anti-Semitic organizations” with the explicit goal of overthrowing the New Deal and rolling back the gains made by working people [23]. The League subsidized “the openly Fascist and anti-Semitic Sentinels of the Republic and the Crusaders, who were urged by their leader, George W. Christians, to consider lynching Roosevelt” [24].

Many of the leaders of the American Liberty League were Democrats who previously supported FDR but turned their backs on him when he began making small steps toward serving the interests of the people [25]. Its directors included Al Smith and John J. Raskob. Smith, who had served as Governor of New York and the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate in 1928, sought the 1932 Democratic presidential nomination, but he was defeated by FDR. Raskob was a financial executive for DuPont and General Motors who had served as chairman of the Democratic National Committee from 1928 to 1932, during which time he had been one of Smith’s key supporters. They were joined in the Liberty League by John W. Davis, who had been the Democratic candidate for president in 1924 and then served as the founding President of the Council on Foreign Relations and worked as an attorney representing some of the largest U.S. companies, including serving as Morgan’s chief attorney.

The League’s Treasurer was Grayson M.-P. Murphy, senior vice president of Guaranty Trust Company and Founder of G.M.-P. Murphy & Co., who also served on the boards of directors of Anaconda Copper, Goodyear and Bethlehem Steel, amongst others. He had the distinction of having been “decorated by Mussolini and made a Commander of the Crown of Italy,” and he was responsible for having raised a significant portion of the financial support necessary to launch the American Legion in 1919 [26]. Other major figures included Sewell L. Avery (a Crusader adviser), W.S. Carpenter, Jr. (who had ties to the DuPont and Morgan Interests), Robert Sterling Clark (heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune), and three members of the DuPont family (Irenee, Lammot and Archibald) [27].

The League set up a National Executive Committee and a National Advisory Council made up of the upper echelons of American industry. George H. W. Bush’s father, Prescott Bush, who had close relations with the new Nazi government in Germany, served as one of its key liaisons. According to Michael Donnelly, “Money was funneled thru the Sen. Prescott Bush-led Union Banking Corporation […] and the Prescott Bush-led Brown Brothers Harriman […] to the League (and to Hitler, but that’s another story). The plotters bragged about Bush’s Hitler connections and even claimed that Germany had promised Bush that it would provide materiel for the coup” [28]. Many of the other leading capitalists behind the plot had investments in Nazi Germany and, according to Christopher Simpson’s detailed analysis, “a half-dozen key U.S. companies—International Harvester, Ford, General Motors, Standard Oil of New Jersey, and du Pont—had become deeply involved in German weapons production” [29].

The League hired Gerald G. MacGuire, an employee of Murphy’s brokerage firm, and one of the founders of the American Legion, to travel to Europe and study various forms of fascism in order to identify the model most applicable to the U.S. He spent four months on his research tour, exploring such things as the Italian fascists’ use of veterans as an important but scantly paid backbone for the fascist movement, and Hitler’s solution to unemployment in Germany (forced labor camps). Although there was much to learn from these movements, and MacGuire supported using veterans and implementing Hitler’s unemployment plan in the U.S., he found the optimal model in France’s Croix-de-Feu: a fascist organization composed of some 500,000 commissioned and non-commissioned officers [30]. Since each officer was the leader of about ten others, the Croix-de-Feu controlled a voting base of some 5 million people according to MacGuire [31]. He explained his intentions to reporter Paul Comly French in no uncertain terms: “We need a Fascist government in this country […] to save the Nation from the Communists who want to tear it down and wreck all that we have built in America” [32]. In order to accomplish this ruling class objective, he was convinced, along with the other plotters, that they needed a charismatic “man on a white horse” to serve as the face for the secretly funded “popular movement.”

The plot

MacGuire considered General Smedley Butler to be the ideal leader of such a movement, due to his excellent public reputation and his wide support among the veterans, but his backers were also considering General Douglas MacArthur, Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., former Legion Commander Hanford MacNider, and James E. Van Zandt (the national commander of the Veterans of Foreign Wars). The latter told reporters that “he, too, had been approached by ‘agents of Wall Street’ to lead a Fascist dictatorship in the United States under the guise of a ‘Veterans Organization’” [33]. He confirmed, as well, that the other members of the military establishment listed above had been contacted in this regard. The reactionary radio personality and fascist supporter, Father Coughlin, said that he had also known of the plans with Butler six months prior to the story breaking in the press [34].

There appears to have been, moreover, a parallel and perhaps overlapping plot involving wealthy financier Jackson Martindell and his Wall Street partners. According to Captain Samuel Glazier’s censored testimony before the McCormick-Dickstein Committee, which will be discussed below, Martindell had contacted him regarding the possibility of leading a Nazi-style organization to overthrow the U.S. government. Martindell’s plan was to have Glazier promise industrial jobs to young white, male workers in exchange for forming an organization, under his command, that would topple the government and establish a dictatorship. Once this was done, Jews and women were to be fired from industrial jobs to make room for the fascist recruits. Martindell praised Hitler in their discussions, whom he said he had met personally on a trip to Germany, and he showed Glazier an arm band with a swastika he had procured. He also shared with him his plans for the insignia and fascist paraphernalia to be used for the new organization:

“Instead of a swastika it was a red eagle on a blue background with a ‘V’ superimposed right through the entire eagle, which was supposed to mean the American Vigilantes. He had a flag, too, that they were in the process of making and he also showed me a membership card which a man was to sign in order to belong to this particular organization. On the back of this membership card it said, roughly, that ‘I swear to uphold the Constitution of the United States and the President’—things of that sort—‘And to get rid of all undesirables and criminals.’ Nothing said at all about who the undesirables were. But he went on further to explain that the word ‘undesirable,’ in that sense, meant Jews” [35].

Returning to the primary plot, what the Liberty League conspirators were looking for was a Mussolini-like figure whom they could discretely pay behind the scenes to do their bidding by mobilizing veterans into a fascist army that would pressure President Roosevelt into accepting their chosen leader as a “secretary of general affairs.” Using the pretext that the President was ill and needed help, MacGuire’s handlers planned on forcing FDR to become a symbolic figurehead like the King of Italy, thereby ceding power to their strongman. According to Butler’s later testimony, MacGuire told him that they could easily control the narrative because they owned the press: “You know, the American people will swallow that. We have got the newspapers. We will start a campaign that the President’s health is failing. Everybody can tell that by looking at him, and the dumb American people will fall for it in a second” [36].

MacGuire explained to Butler that he had $3 million available for the plot, and that he could get as much as $300 million from his backers if they needed it. As he told reporter Paul Comly French, he could “go to John W. Davis or Perkins of the National City Bank, and any number of persons to get it” [37]. Robert Sterling Clark also sought to reassure Butler that money was not an issue because he was personally “willing to put up $15,000,000 to save the other $15,000,000” [38].

Since the government refused to give the veterans pensions or anything of the kind, the plan was to use some of this money to provide them with pensions in order to bait them into supporting their plan to overthrow the government. When Butler responded to MacGuire that providing pensions would require a lot of money, the latter further specified that “we will only have to do that for a year, and then everything will be all right again” [39]. The plan was thus to lure the impoverished veterans into creating a public spectacle that would appear to be organically populist, mirroring the Bonus Army March, and then abandon them financially once power had been secured for a new fascist leader.

The astroturfing capitalist schemers behind MacGuire also had concrete plans for arming their fascist army of veterans. Since the Du Ponts owned a controlling interest in Remington Arms Co., they knew they could easily obtain a large quantity of weapons on credit [40].

A major segment of the capitalist class thus conspired to use its financial resources, network of elite operators, and control of the media to hire a charismatic leader, raise and arm a fascist militia of poor veterans, overthrow the elected government, and establish a fascist dictatorship in order to roll back the New Deal and thereby increase their profits. If they had succeeded in doing so, it is arguable that the history of the 20th century would have been remarkably different.

Failed plot, nearly successful cover-up

Rumors had been circulating in Washington that “the American Legion was going to provide the nucleus of a Fascist army that would seize the Capital [sic]” [41]. The McCormack-Dickstein Committee, which was the first House Un-American Activities Committee, decided to investigate. Although General Butler had been having ongoing conversations with MacGuire and Clark, allegedly in order to learn more about their financial backers and plans, he had also been becoming increasingly aware—as communist critics were saying at the time—of his social function as a paid gangster for the capitalist class. Having already involved journalist Paul Comly French in his discussions with the plotters in order to have a reliable witness to corroborate his claims, Butler decided that it was best to go public with the plot and speak out against their plans for a fascist overthrow of the government.

Major General U.S. Marine Corps Smedley Darlington Butler Speaks Out Publicly against the Fascist “Business Plot” on November 21, 1934

The McCormack-Dickstein Committee, in its investigation, ran a faith-in-government campaign not dissimilar to those undertaken by other governmental committees in bourgeois democracies. On the one hand, it presented itself as an objective investigatory body intent on getting to the bottom of the potential plot and rooting out any malfeasance. On the other hand, it did nearly everything in its power to protect the plotters, avoid serious investigations of the evidence, and eschew any systemic critique of the capitalist establishment. In this regard, it:

- Did not call any of the conspirators to testify (with the exception of their pawn MacGuire), dismissing allegations against the capitalist ruling class and the top brass of the military as “mere hearsay” that did not merit investigation.

- Censored from its report the most revealing parts of the testimony that was heard, particularly those that pointed to the true culprits and explicitly named the companies, financial interests and individuals involved [42].

- Attempted to ideologically shift the focus of the hearings by turning its attention to the investigation of charges that “some left-wing unions had used a three-million-dollar fund to ‘foment and carry on strikes’” [43].

- Did not pursue any prosecutions of the conspirators.

Nevertheless, Butler’s claim that there was a fascist conspiracy to overthrow the government was confirmed by the Committee, which heard corroborating testimony from journalist Paul Comly French and military official James E. Van Zandt. Although MacGuire denied the major claims of a conspiracy, while admitting to having had meetings with Butler, the Committee “found five significant facts that lent validity to Butler’s testimony” [44]. In particular, MacGuire could not explain what he had done with all of the money he had received [45]. The committee also uncovered evidence that disproved a number of MacGuire’s assertions [46]. It thus reached the conclusion that there was indeed a conspiracy.

However, as reporter George Seldes explained, “most papers suppressed the whole story or threw it down by ridiculing it. Nor did the press later publish the McCormack-Dickstein report which stated that every charge Butler made and French corroborated had been proven true” [47]. Instead, the bourgeois press organized a vast smear campaign against Butler in order to depict his testimony as a hoax or a mendacious fabrication.

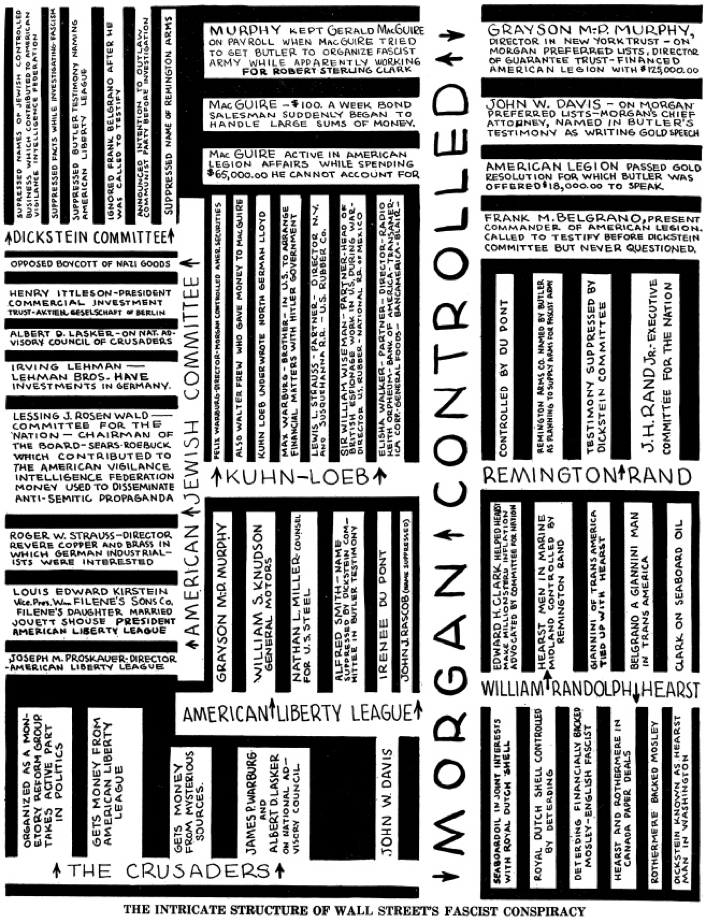

It is thanks to the communist journalist John L. Spivak that we now have a more complete transcript of the testimonies before the McCormack-Dickstein Committee. When he was given permission to study HUAC’s public documents, he had been provided, apparently unwittingly, with the uncensored testimony amid stacks of other papers. In an explosive two-part exposé that he went on to write for the Communist Party’s New Masses in January 1935, “Wall Street’s Fascist Conspiracy,” he revealed that the congressional committee had deliberately suppressed evidence and censored testimony “because financial powers behind the committee are among the supporters of fascist organizations” [48]. More specifically, he demonstrated that the American Liberty League was controlled by the Du Pont interests, “which are tied up with Morgan interests and Morgan interests are tied up with Warburg interests and Warburg interests control the American Jewish Committee which in turn guided this Congressional body” [49].

In spite of all of the evidence and the clear conclusion of the Committee, none of the plotters ever faced prosecution. “Powerful influences,” wrote Jules Archer, “had obviously been brought to bear to cut short the hearings, stop subpoenas from being issued to all the important figures involved, and end the life of the committee” [50]. Roger Baldwin, Director of the American Civil Liberties Union at the time, issued an angry statement that underscored the hypocritical nature of this outcome:

“The Congressional Committee investigating un-American activities has just reported that the Fascist plot to seize the government… was proved; yet not a single participant will be prosecuted under the perfectly plain language of the federal conspiracy act making this a high crime. Imagine the action if such a plot were discovered among Communists! Which is, of course, only to emphasize the nature of our government as representative of the interests of the controllers of property. Violence, even to the seizure of government, is excusable on the part of those whose lofty motive is to preserve the profit system” [51].

Gangster capitalism at home and abroad

The failure of the planned fascist seizure of state power in the U.S. marked a clear victory for working people, as well as for everyone who fought for and benefited from the New Deal. It fell through, in the words of John L. Spivak, not only because “the conspirators were incredibly incompetent in picking [Butler],” but also because they “lacked an elementary understanding of people and the moral forces that activate them” [52]. This failure, however, did not signal an end to the capitalist ruling class’s support for fascist movements, both domestically and internationally.

Butler had been radicalized by this experience, inspired amongst other things by the courageous militant actions on the part of the Bonus Army, and increasingly disheartened by the reaction of the henchmen of the capitalist rulers. As he began increasingly to see the bigger picture and recognize—at least implicitly—the correctness of communist analysis, he spoke out against the political economy of war, recognizing that a second major international conflict was looming on the horizon.

As early as 1931, as he spelled out in a speech to the American Legion, which apparently had not been taken very seriously by his handlers, Butler realized that his role in the military amounted to nothing more than serving as a global gangster for the capitalist class:

“I spent thirty-three years and four months in active military service, and during that period I spent most of my time being a high-class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Honduras right for the American fruit companies in 1903. I helped purify Nicaragua for the International Banking House of Brown Brothers in 1902–1912. I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. In China in 1927 I helped see to it that Standard Oil went on its way unmolested. Looking back on it, I might have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three districts. I operated on three continents” [53].

Thus, while an open fascist dictatorship had been avoided on the home front, and the workers’ movement continued to make significant gains within bourgeois democracy, the U.S. imperial war machine pursued its operations abroad, and the public-private partnership to violently destroy communist organizing continued along with Jim Crow on the home front, aided and abetted by the Ku Klux Klan and other fascist or semi-fascist organizations. Averting an overthrow of the government and forcing the political establishment to instead forge ahead with the class compromise of the New Deal was a major victory for many working people, and it should be recognized as such. As long as the capitalist system persists, however, it will continue to have recourse to fascist movements and dictatorial regimes as its ultimate weapon of class war. They will only be eliminated once and for all when their root cause is destroyed: capitalism.

This foray into the history of U.S. fascism, while providing important perspective on the storming of the Capitol that was our point of departure, should not lead to the facile conclusion that fascism in the 1930s is identical to its 21st-century forms, or that there is a strict analogy between the “business plot” and January 6th. However, the project of elucidating this particular history of fascism, which is on the public record, is important for understanding the variety of tactics that the bourgeoisie uses to try and maintain, at all costs, its ability to accumulate at the expense of the working and toiling masses. This historical knowledge can help orient us in our present and future struggles.