December 2018 marked the 100-year anniversary of the slaughter of striking typographers and workers of Bucharest, Romania. More than 15,000 men, women and children — workers from all factories –– filled the streets on Dec. 13, 1918 in solidarity with the typographers. Their demands: an 8-hour work day, a living wage and recognition of the workers’ union.

Fearing the spread of the Russian Revolution from the year prior, the government sent in the military to attack the peaceful demonstrators. More than 100 were killed, and many thousands were wounded, or arrested and tortured. The brutality shook the population of the country. At the time, the government expected this would quell the uprising, but on the contrary, solidarity actions were called in every part of the country and the workers’ movement of Romania grew.

The first devastating World War

1918 was a year of upheaval in Romania: The imperialist First World War was drawing to a close, and the German occupation of Bucharest had left the country in shambles. More than 700,000 soldiers and civilians were killed during this time.

Romania was ruled by a constitutional monarchy that represented two bases: the moshieri-boyar (nobility) from the countryside and the newly-formed capitalist class that controlled the urban factories and other industry. Similarly, the working population of the country was split between the tzarani (peasants) and the urban workers.

The situation for urban workers was very difficult. Their entire livelihoods were at the discretion of the business owners. Workers––including children as young as six––worked from 12 to 16 hours per day. Between the years of 1917 to 1920, living conditions were reduced to 1/3 of what they were before. At this same time, the profits of the capitalists soared by 190%. The few political rights the workers had were won through struggle, and these were under continual attack by the ruling class.

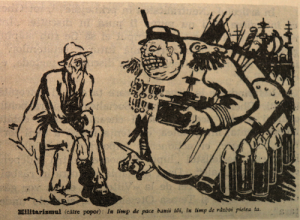

This 1914 political graphic from “România Muncitoare” depicts a military general mocking the starving working class. The general is saying to the people: “In times of peace we take your money, and in times of war we take your hide.”

World War I gave the government an excuse to brutally repress any protest of workers against the factory conditions. Newspapers airing workers’ grievances were shut down. In many factories the owners would beat their workers, and when this was not enough the state set up military prisons alongside industrial factories. Military tribunals sentenced scores of socialists and union organizers to decades in prison.

The situation of the peasants was not much better. Half of all arable land was owned by just 5,383 nobles. Out of more than 1 million families, only 1/4 owned enough land to feed themselves. Many peasants did not own their own equipment and lacked access to agricultural credit, forcing them into near serfdom through the high rents and interest to the landowning class.

‘We are surrounded by revolution, and we do not believe we will remain isolated like an island’

Under these oppressive conditions, the movement for socialism grew. The October Revolution just one year before showed that it was possible to create a workers’ state. Strikes and other revolutionary activity sparked throughout the country through the slogan, “Long live the Russian Revolution!” In fact, the unions and the socialist movement were inseparable, as many union organizers were socialist leaders. Agitational pamphlets and socialist newspapers put together by typographers played a vital role in this process.

Before the advent of digital communication and printing, every letter in books and newspapers had to be set by hand. News simply could not be distributed without the complex work of the typographers, though they faced many obstacles doing so. Every legal newspaper employed a censor who would erase content deemed revolutionary.

The first days of December 1918 witnessed a rapid growth and intensity of strikes across all sectors of workers. On Dec. 1, the same day the king returned from exile, 6,000 railway workers walked off their jobs for a strike in Bucharest. Two days later, the 5,000 administrative workers of the government also went on strike.

Panicked by the growth of the socialist movement, the liberal government tried to sow division with revolutionary Russia through the press. Typographers were instrumental in tripping up the development of the anti-Soviet campaign, refusing to print the government’s slander against Soviet Russia.

Revolution was everywhere. As socialist leader Gheorghe Cristescu wrote on Dec. 1, 1918, “Every worker is turning their sights towards the sunrise in Russia. We can see our salvation through the destruction of capitalist society. We are surrounded by revolution, and we do not believe that we will remain isolated like an island.”

In Bucharest, working conditions for the typographers had deteriorated apace with other urban workers. The typographer-run newspaper Unirea Grafica noted on Dec. 9, 1918, “The factory owners know that with the salaries today, we typographers can barely afford daily necessities. And now in the winter, they want to lower our wages and suppress our very existence.”

Typographers’ strike: ‘Long live the Russian Revolution’

On the evening of Dec. 12, delegations from the typographers’ unions and workers’ guilds gathered in the capital, and together announced a general strike. Among the initiators of the strike were socialists Ilie Moscovici, Gheorghe Cristescu, Ion Costache Frimu, Christian Rakovsky and Ana Pauker. Their demands were: an 8-hour work day, a living wage, an end to the censorship, and legal recognition of their unions. The factory owners were well aware of these demands but refused to negotiate.

The government prepared the military for an attack. Enticing the soldiers with food and alcohol, the generals told them they were fulfilling “a great historic act.” They stationed troops around union offices and the plaza of the National Theater, where workers would converge. An hour before the demonstration, officers ordered the merchants of the nearby Ion Campineanu Street to close their shops and draw their shutters.

On the chilly morning of Dec. 13, 1918, 600 typographers left the printing presses and gathered on the Ion Campineanu Street. They were met by 15,000 workers from other industries, who heeded the call of the socialists to join the strike in solidarity. The workers organized themselves into columns, and began marching down Calea Victoriea Street towards the Ministry of Industry and Commerce to hand the minister their list of demands.

Finance minister Vasile Cancicov wrote about this incident with panic:

“Are we on the eve of Bolshevism? This morning at 8, I walked by Calea Victoriea Street and I saw the Ministry of Industry completely surrounded, from the court to the street, by a turbulent multitude of people. They were the strikers. No sign of the authorities.”

The socialist manifestation induced the government into panic. Cancicov continued:

“From the main entrance gate waved an immense red flag. A red banner of several meters’ length was hung from the door, and on which was written in large letters, Long live the Socialist Republic! Red placards were stuck all along the walls of the building, and along the iron fence, reading: Down with the boyars! Down with the capitalist bourgeoisie! Long live communism!”

The Ministry refused to acknowledge the workers’ demands, and so the columns continued onto the chosen plaza of the National Theater. Interestingly, on the way back the crowd ran into the car of the monarch, Ferdinand I, whose driver ordered the people to make way for the king. Instead, the many people forced the royal car to stop as they continued their march, calling out, “Down with the monarchy!”

Despite all of their concentrated military might, the ruling class trembled in the face of the developing organization.

Never before had the streets of Bucharest witnessed such an event: unending streams of men, women, and children joining in the struggle together. They cried out, “Long live the Russian Revolution;” “Land for the peasants;” “We want an 8 hour work day;” and “We need bread!” Many sang the Internationale. Workers from the gun factories, administrative offices, car manufacturers, and railway yards all made their way from every corner of the capital towards the center to join the strike.

When the columns reached the Theater, the army attacked. Soldiers opened fire upon the unarmed, striking workers. People fell dead and wounded, but the column of workers could not be stopped. The first round of soldiers balked and broke apart, and immediately fresh troops were brought in. Soldiers stabbed men, women, and even children with swords and kicked them in the face. They slaughtered more than 100 people.

In this 1919 photo from Frimu’s funeral, the people gather under a banner reading “Down with the assassins of Frimu!”

After the plaza was bathed in blood, the soldiers were ordered to march to the union offices. They ransacked the building and arrested every worker they found, including socialist Ion Frimu, who was horribly beaten and thrown in prison, along with more than 2,000 others. Frimu would die from his wounds in prison several weeks later.

Vans carried the dead to the cemetery the entire night, throwing the bodies into a mass grave. Only seven people were identified. Everyone had a family member or friend who was arrested, wounded, or dead.

The persecution of workers intensified, and workers’ newspapers were suspended. King Ferdinand I decorated General Margineanu, the organizer of the bloodbath, and warmly embraced him. Bourgeois newspapers attacked the workers as “Bolsheviks,” and claimed that only 6 people had been killed.

Yet despite the increased hardships, the typographers continued their strike, and the movement grew. The government’s attack only further provoked workers into action. Typographers flooded into the unions by the thousands, and the many separate unions joined together. Workers from all industries saw the struggle of the typographers as directly connected to their own. They also understood that solidarity with Soviet Russia, which the typographers had undertaken, was the fight of all workers in the country.

In his last letter from prison, Ion Frimu wrote to his comrades to continue the struggle not just for the freedom of those arrested, but for the liberation of all. “During low points of the struggle of the masses,” Frimu wrote, “the communist avant-garde must make even greater sacrifices. These sacrifices are the link between two revolutionary waves. This does not mean ‘heroism’ or ‘martyrdom’, but rather simply, that these sacrifices are what is necessary.”

Aftermath and legacy

After only a few days the railway workers joined the strike, followed by other industries. Ultimately, the typographers won their demands of an 8-hour day and an increase in salaries.

Strikes and other revolutionary actions proved instrumental in the development of socialist consciousness of the working class. The masses of workers, previously unorganized, now aligned themselves against the government that attempted to crush the revolutionary wave.

Unions, as the events of Dec. 13 showed, were key to the development of socialism. As I. Felea wrote in the typographers’ newspaper Munca Grafica one year later:

“What is the role of the union? The union is nothing more than a medium for socialist ideas to take root in the masses. Economic demands won through struggle are nothing more than successes that help us more easily and more rapidly smash the citadel of capitalism.”

The union makes life less bitter, Felea noted. But typographers had a special duty to be at the forefront of the revolutionary struggle. “We need to move beyond the union struggle with a limited scope that just preserves us as individuals,” he wrote, “so that we can give our fight a revolutionary character. It is a fight to negate the dominion of the bourgeoisie, and to make working people control production.”

When the Soviet Red Army liberated Romania from the pro-Nazi fascist dictatorship of Ion Antonescu in 1944, Romania went through a period of socialist development until the counterrevolution of 1989. During those years, December 13th was designated as a national holiday–-Typographers’ Day–and a mausoleum that honored revolutionary Ion Frimu and others was established in Tineretului Park. The socialist government mounted a commemorative statue and plaque in front of the National Theater, the location of the slaughter. Even the street the revolutionaries marched down was renamed to Strada 13 Decembrie 1918.

Capitalism restored, history erased

With the restoration of capitalism in the 1990s, monuments to fallen revolutionaries became inconvenient reminders. The body of Frimu and other socialists were disinterred from the mausoleum in Tineretului Park and relocated to various cemeteries throughout the city. The new anti-communist crusade reverted the name of Strada 13 Decembrie 1918 to Strada Ion Campineanu, and the monument in Tineretului was dubiously rechristened for the “unknown soldier.” The commemoration of the “unknown soldier” is indicative of the far-right orientation of the now “democratic” Romania.

The author attended the centenary commemoration of the Typographers’ Revolt in Bucharest, organized by the Partidul Socialist Român and the Partidul Comunitar din România. Both organizations also restored the memorial, which had fallen into disarray. Long live the workers’ struggle! Photo: Liberation School.

Even the plaque commemorating the revolt in front of the National Theater was torn down and replaced with a digital casino billboard. And finally, the capitalist government scrubbed the history books to erase every trace of Romania’s revolutionary class struggle. Romanian students today never learn of the events of Dec. 13, 1918, and most have never heard of Ion Frimu, Christian Rakovsky, or any of the revolutionaries who led the vanguard movement decades before Romania’s fascist dictatorship was overthrown.

Everywhere that class society has existed, people have organized and fought back. Romania has a rich history of struggle by socialists and unionists; a shining example of which is the struggle of the Typographers’ Revolt. Their dedication and sacrifices continue to inspire and teach us to this day.

Long live the revolutionaries of December 13! Long live the struggle for socialism!

Sources

Alexandrescu, V. I. “Ca sa se stie”. Unirea Grafica. 9 Dec 1918.

Felea, I. “Lupta economica si lupta politica”. Munca Grafica. 22 Dec 1919.

Frimu, I. C. Ultima scrisoare adresata de I. C. Frimu tovarasilor sai inainte de a fi trimis la spital de la inchisoarea Vacaresti. From Nicolae Petreanu and Dan Baran. I.C. Frimu, Evocari: Studiu si antologie. Editura Politica. 1969

Georgescu, N. I. “13 Decembrie”. Munca Grafica. 26 Dec 1919.

Stoica, Gheorghe. Luptele din 13 Decembrie 1918. Partidul Muncitoresc Roman. 1952.

Racovski, Cristian. Sindicatele muncitoresti (Rolul si istoria lor). Conferinta tinuta in Sala Cercului “Romania Muncitoare” din Bucuresti in ziua de 25 Iunie 1906. Cercul de editura socialista. 1920.

Agragul. “Evenimentele de joi.” 16 Decembrie 1918